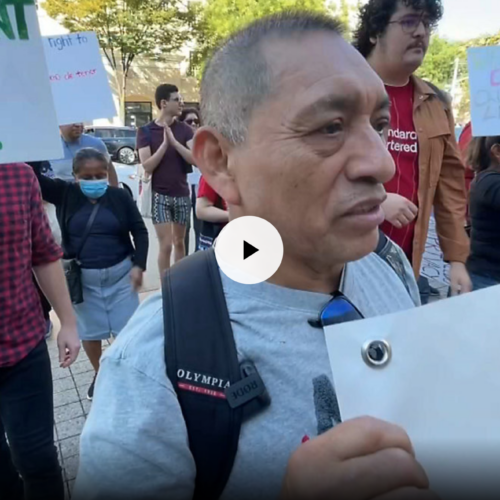

Woodside Rallies for Tenants’ Rights: A Push for Statewide Legal Counsel in Eviction Cases

In the News – Woodside Rallies for Tenants’ Rights: A Push for Statewide Legal Counsel in Eviction Cases February 25, 2024 By Nimrah Khatoon, BNN Breaking Discover the transformative power of legal representation highlighted at the ‘Queens United: Town Hall